A Literature Review to Narrow the Search

“This was an issue we encountered when we started investigating the potential for biocontrol of hibiscus bur (Urena lobata) in Vanuatu,” said senior researcher Quentin Paynter. Hibiscus bur is a small shrub with pink, hibiscus-like flowers. It is invasive in Vanuatu, where it outcompetes pasture grasses, affecting the local beef industry. The New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (MFAT) funded a biocontrol programme in 2018 to target this species in Vanuatu. It had never previously been targeted for biocontrol.

Image: hibiscus bur infestation in Vanuatu.

“Hibiscus bur is found throughout the tropics, and we weren’t even sure which continent to survey for natural enemies, let alone which country or region!” said Quentin. “Some authors suggest it is native to Africa, some Asia, but Plants of the World Online, published by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, indicates that it is native to the Caribbean Islands, Central and South America, Africa, and Asia west of the Wallace Line. Comparing genotypes can potentially match native and exotic populations, but at the start of the programme plant samples weren’t available for analysis and we couldn’t wait for a genetic study to be conducted,” he added. Quentin then suspected that literature searches could help identify regions with the highest diversity of specialist natural enemies and therefore indicate where to survey for candidate biocontrol agents.

Plant pathogen host records were sourced from the US National Fungus Collections Fungal Database. This database enables the name of a host plant to be entered, and the output produces a list of fungus species that have been recorded using that plant as a host, plus the location (e.g. country) where each observation took place. To assess the potential host specificity of the pathogens identified, the database was further interrogated. The names of each pathogen recorded attacking hibiscus bur were entered to obtain a full list of host records for each pathogen. Fungal pathogens were defined as specialist (host records confined to the genus Urena), oligophagous (records from several genera in the plant family Malvaceae, to which Urena belongs), or polyphagous (host records include plants belonging to other plant families). A similar approach was taken for arthropods, although there is no single source of host record data for phytophagous invertebrates. Records were located using online databases, where available (e.g. for Lepidoptera), and by using online searches using the terms “Urena lobata” and “host plant”.

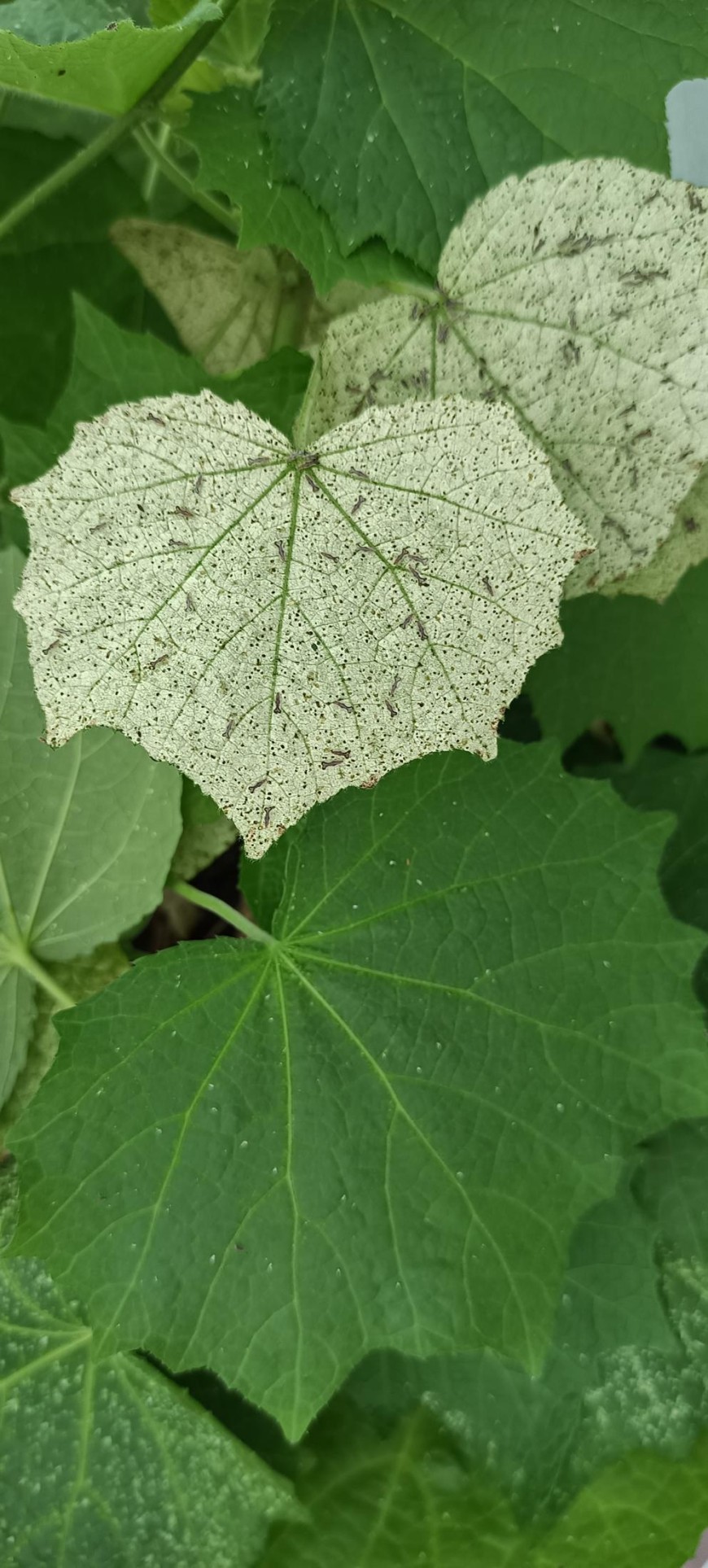

Image: lace bugs on hibiscus bur leaves.

Quentin noted that comparing the numbers of potentially host-specific natural enemy species in different regions can be misleading due to observational bias (the fauna of some regions is likely to have been more thoroughly investigated than others). “I assumed that even if the number of species recorded in different regions might be subject to observational bias, the proportion of potentially host-specific species within different regions should be independent of the number of records. Consequently, the analysis tested whether the proportion of potentially host-specific species varied between regions,” he explained.

The geographical resolution of host records was often low (e.g. to country level only), and there weren’t a lot of records. Consequently, to analyse the distribution of species that attack hibiscus bur, the resolution had to be broad. Records were allocated to the three biogeographical realms where Plants of the World Online indicates that hibiscus bur is native: the Neotropical, Afrotropical, and Indomalayan realms.

The analysis indicated that the proportion of potentially host-specific natural enemy species present varied significantly between realms: three (c. 14%) natural enemy species recorded feeding on U. lobata in the Afrotropical realm are potentially specific to the genus Urena, compared to 13 species (c. 22%) in the Indomalayan realm and none in the Neotropical realm. The absence of specialist natural enemies throughout the Neotropical distribution of hibiscus bur indicates that it is not native there. Although the diversity of apparently specialist natural enemies was highest in the Indomalayan realm, the data do not exclude the possibility that hibiscus bur is also native to Africa. Nevertheless, the relative abundance of records of potentially host-specific agents from the Indomalayan realm suggested that this is the more promising region to begin surveys.

Where to survey was further refined by very simple climatic matching: The Köppen climate classification divides climates into five main climate groups, with each group further divided based on patterns of seasonal precipitation and temperature. Vanuatu is classified as having an Af Tropical Rainforest Climate. Within the Indomalayan realm, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines (and small parts of Thailand and Sri Lanka) have the same Af climate classification as Vanuatu

Based on the results of this study, it was recommended that:

- surveys for natural enemies of hibiscus bur commence within the Indomalayan realm, focusing on countries that have the same Af climate classification as Vanuatu

- concurrent collection of plant samples should be made in Vanuatu and in surveyed regions, and additional herbarium samples sourced, if required, to conduct genetic matching to ensure candidate agents are sourced from plants that belong to the same biotype as those that occur in Vanuatu, where biocontrol is required.

Subsequent work was severely disrupted by Covid-19, but surveys were conducted in Malaysia in 2019, before the pandemic, with the assistance of researchers at the Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI). A tingid bug (Haedus vicarius) was prioritised for further investigation because there are reports of this species inflicting severe damage to hibiscus bur in Southeast Asia. A shipment of the tingid bug was couriered from Malaysia to containment in Auckland in February 2021, and subsequent testing confirmed that it is sufficiently host specific to release in Vanuatu. Permission to release it there was granted in April 2024 and the first releases took place in late July 2024.

Molecular work conducted by Caroline Mitchell subsequently indicated that hibiscus bur growing in Vanuatu is a good genetic match to plants in Malaysia, validating the literature review findings. “At the start of the programme I thought finding an agent of hibiscus bur might be mission impossible,” Quentin said. “I can’t quite believe how well the approach worked, and examining host records in the literature is likely to become easier as more host records become available online and as taxonomic uncertainties (e.g. surrounding cryptic species) are resolved. Who knows, maybe we could even use AI to do this for us in future!” he added.

Image: lace bug release demonstration in Vanuatu.

This work was funded by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (Activity PF 10-582), and the writing of this manuscript was supported by core funding to Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research from the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment.