Accidental introduction of cleavers mite

Image: damage from the cleavers mite.

For example, a European migrant, the hemlock moth (Agonopterix alstromeriana), was first recorded in New Zealand in 1986 and now often completely defoliates invasive and poisonous hemlock, an introduced weed. Similarly, a rust fungus (Melampsora hypericorum), has major impacts on populations of tutsan (Hypericum androsaemum), an introduced invasive shrub, in the South Island. Neither have been reported to attack any other plant species in New Zealand and appear to be highly beneficial accidental introductions.

Nevertheless, senior researcher Quentin Paynter cautioned against the indiscriminate use of accidentally introduced organisms in New Zealand. “Although these examples appear to be wholly beneficial additions to New Zealand’s fauna, accidentally introduced species are unlikely to have undergone the level of scrutiny that deliberately introduced biocontrol agents are subject to, and we would want to be absolutely certain that an organism is host specific before considering redistributing it.”

Quentin also noted that there is a regulatory process that needs to be followed to change the status of a new organism that has become established in New Zealand. Attempts to redistribute an organism that has not had its status as ‘new’ removed will contravene the Hazardous Substances and New Organisms (HSNO) Act, even if its impacts appear to be beneficial.

In June 2017 cleavers plants (Galium aparine, also known as goose grass) that were displaying extensively curled leaves were discovered in Auckland. These symptoms were found to be the result of attack by an eriophyid mite Cecidophyes rouhollahi (henceforth ‘cleavers mite’). Since then, symptomatic plants have been found throughout New Zealand, from the Bay of Islands to Fiordland and Otago. The cleavers mite is still classified as a new organism in New Zealand, but it is already so widespread that any question about whether we should augment or slow its dispersal is moot. But is it likely to be a beneficial addition to New Zealand’s fauna?

Globally, the cleavers mite was first recognised in the 1990s as a separate species, distinct from the very similar, closely related mite, Cecidophyes galii. Confusion between the cleavers mite, C. rouhollahi, and C. galii has occurred in the past; for example, pictures of specimens identified as C. galii collected from Gallium species from Finland and England in the 1950s appear to be of cleavers mites (C. rouhollahi). Subsequent investigations indicate that the cleavers mite is widespread in western Europe.

“It’s interesting to speculate how the mite got here,” said senior researcher Simon Fowler, adding that “the stems of cleavers are covered with hooked hairs and feel quite sticky and attach to clothes like Velcro, so it seems quite likely that some infested foliage arrived inadvertently attached to someone’s clothing or belongings.”

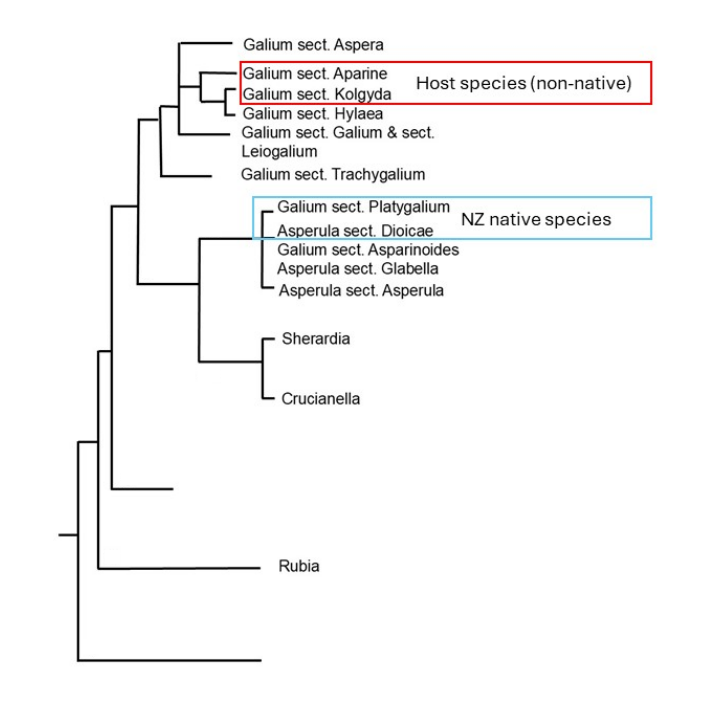

The damaging symptoms caused by the cleavers mite attracted the attention of weed biocontrol researchers, who were interested in its potential to control false cleavers (Galium spurium), a close relative of G. aparine, which is invasive in North America. Specificity testing conducted at the USDA Agricultural Research Service’s European Biological Control Laboratory in Montpellier, France, indicated that the cleavers mite could only survive and reproduce on three closely related annual species in a section, Kolgyda, of the genus Galium, including G. spurium. The cleavers mite is therefore unlikely to be capable of attacking the Galium species that are native to New Zealand, because these belong to Galium sections other than Kolgyda. (Note that a recent phylogenetic study included G. aparine and G. spurium in section Aparine, which is adjacent to section Kolgyda, and so the conclusion that New Zealand species are unlikely to be hosts is unchanged.) The image (below) of the phylogenetic tree of Rubieae shows the Galium sections that are hosts of the cleavers mite in the red box, and the New Zealand native Galium species in the blue box.

Image: simplified phylogenetic tree of the Rubieae showing the Galium sections.

Following approval, cleavers mites were released in Vegreville, Alberta, Canada, in 2004 and evaluations indicated that they reduced false cleavers (G. spurium) biomass and seed production by c. 30% over the 2004 field season. However, mites failed to reappear during the following field season in Vegreville, or at other release sites in Alberta, and subsequent experiments demonstrated that the mites are not sufficiently cold hardy to survive the bitterly cold Alberta winters. It was concluded that the cleavers mite wasn’t suitable for use as a classical biocontrol agent in Alberta, but that that it might be effective in regions with warmer winters.

“We assume that the cleavers mite is having a big impact on cleavers here in New Zealand,” said Quentin, who noted that most cleavers plants in the Auckland region appear to be galled and are often heavily galled. “Because mite numbers have built up over several years, they may well be having a bigger impact than observed by the Canadian study, which was conducted over just one field season.” Simon agrees, noting that the mite is also very common around Christchurch, where it appears to frequently kill plants completely before they set seed.

MWLR principal scientist Zhi-Qiang Zhang and colleagues Min Ma (Shanxi Agriculture University, China) and Qing-Hai Fan (Ministry for primary Industries, Auckland) have documented the presence of several predatory phytoseiid mite species in association with the cleaver mite in New Zealand, notably Amblydromalus limonicus, which has previously been shown to be capable of surviving and reproducing on a diet of Eriophyid mites.

“We know from this study that predatory mites have taken advantage of the abundant new food source that the cleavers mite provides in New Zealand”, noted Quentin, “but they don’t seem to have much impact on the ability of cleavers mites to gall cleavers plants.”

Quentin also noted that this appears to mirror the situation regarding the broom gall mite (Aceria genistae), which is also attacked by phytoseiid mites but is nevertheless a successful biocontrol agent in New Zealand. “This is probably because the galls they induce are densely hairy and highly convoluted. Small eriophyid mites consequently find refuge from the bigger, predatory phytoseiid mites.”

He continued, “This potential escape from predation bodes well for another eriophyid mite, the old man’s beard gall mite (Aceria vitalbae), which was first released in New Zealand following approval from the Environmental Protection Authority in 2021 and which also induces hairy, convoluted leaf curls.”

Further reading

Craemer C, Sobhian R, McClay AS, Amrine Jr, JW 1999. A new species of Cecidophyes (Acari: Eriophyidae) from Galium aparine (Rubiaceae) with notes on its biology and potential as a biological control agent for Galium spurium. International Journal of Acarology 25: 255–263.

Ehrendorfer F, Barfuss MH, Manen JF, Schneeweiss GM 2018. Phylogeny, character evolution and spatiotemporal diversification of the species-rich and world-wide distributed tribe Rubieae (Rubiaceae). PLoS One 13(12): p.e0207615.

Ma M, Fan QH, Zhang ZQ 2018. An assemblage of predatory mites (Phytoseiidae) associated with a potential biocontrol agent (Cecidophyes rouhollahi; Eriophyidae) for weed Galium spurium (Rubiaceae). Systematic and Applied Acarology 23: 2082–2085.

McClay AS 2013. Galium spurium L., false cleavers, and G. aparine L., cleavers (Rubiaceae). In: Biological control programmes in Canada 2001–2012. Wallingford UK, CABI. Pp. 329–332.